Singapore, the tiny island-nation with famously impeccable streets, not a leaf out of place and constantly updated infrastructure, all maintained by a population of foreign workers who form about a quarter of the population. Beyond the people who clean the streets and trim the bushes, there are foreign domestic workers who maintain the households, and in this community has Balli Kaur Jaswal set her latest novel, Now You See Us.

The household workers are largely Filipina: they scrub the floors, sweep verandahs, do the household laundry and ironing, go grocery shopping, and cook meals, help elderly family members and look after children. They travel far from their home country, often leaving their own children behind. With jobs in Singapore, they can send money and gifts home, hoping to enable a better life for their families in the Phillipines.

Their employers (the “ma’ams”) are well aware of their power:

How can they send me a maid who can’t do anything properly? And then she wants one day off a week. I tell her “You’re a fresh maid, you are here for the experience. You’re lucky to have any work at all.” In their country there are no jobs — even teachers and nurses are only making two hundred dollars a month. Here she gets free lodging and food in my flat [..] and she’s earning in Singapore dollars, and she still complains?[..] Just look at her, give her one look, and you’ll know what type she is and what she’ll be doing on her day off.

This is Mrs. Fann, who embodies the worst characteristics of the employers. She is relentlessly suspicious, infinitely demanding, and very authoritarian.

At the other extreme there is “Ma’am Elizabeth”, who orders Filipina food because she thinks her new maid Cora might be homesick, tells Cora not to bother when she does any work, tips generously, is kind to animals, and tries to treat Cora like a friend, even telling her family secrets.

Cora, Donita and Angel are the three Filipina maids at the heart of this novel. Cora is in her fifties, and is terrified that Ma’am Elizabeth or the dreaded Singapore authorities will discover the reason she left Manila. Donita is young, pretty, and dresses in body-baring, attention-attracting clothes; she rebelliously ignores Mrs. Fann’s strictures about clothing.

“This is who I am. If she doesn’t like it, that’s her problem.”

Angel works for an elderly Indian man, Mr Vijay, who is recovering from a stroke. His son Raja “lingers too close” for Angel’s comfort, and she is also worried about the new nurse invading her territory.

Despite the tight rein kept on the maids, there are opportunities for romance. Donita falls for an Indian construction worker, Sanjeev, and they manage romantic interludes in by-the-hour hotels before curfew. Angel is recovering from a bad breakup, but she is cautious who she tells, since her ex- is a woman.

Surveillance is continuous. Mrs Fann ‘makes [Donita] stand with her legs and arms spread to check if Donita had taken anything.’ The police have full authority to demand ID cards and information or search their personal belongings. There are watchful eyes everywhere: WhatsApp groups of employers who post pictures of each others maids in ‘suspicious’ situations.

Does this maid belong to you? I saw this Filipina talking with some foreign workers. [..] Worse, she had a child with her! Didn’t get her name but here’s a picture.

There are periodic snippets from this Whatsapp group at the end of the chapters, and they are reliably unpleasant. Women complaining that the maids who insist on a day off (as per the law) are “so lazy and unmotivated”. Women refusing to share the household Wifi with maids who want to talk to their children in the Phillipines. They sound very authentic:

must draw a line otherwise these women will climb on our heads

it’s the bus auntie’s word against hers

Beyond the race and class hierachy, the author adds complexity to the interactions. Cora, for example, is deeply uncomfortable with Ma’am Elizabeth’s attempts to treat her as a friend; a lunch together in a nice restaurant is a tortuous social minefield for Cora, what with the waiters regarding her suspiciously and her worries about what and how much to order. Eventually she says:

I just want to do my job, not go out and share my life with you.

Cora’s previous employers made

the mistake of assuming that all household help would get along, but there were hierarchies and histories.

This novel is largely a commentary on the status and lives of Singapore domestic workers, but it is also framed around a murder based on the real-life story of Flor Contemplacion who was executed in 1991. In this novel, a maid called Flor has been arrested for the murder of her employer. Flor is a friend of Cora, Donita and Angel, and they leap into action to find the true murderer.

The amateur-detective thread is less convincing than the main social commentary, and the novel flags as the murder story gets more prominent towards the end. More complex is the slow exposure of Cora’s secret, which is tied to Duterte’s War on Drugs. Angel’s lesbianism is described several times, but without a lot of nuance. Side stories about anti-gay churches are distracting.

The writing is quite smooth and pleasant, without being remarkable:

The sun is a boiling yolk over the island, and even the outstretched tree branches are unable to keep the concrete driveway from baking.

The author’s heart is in the right place, and the novel very clearly underlines the vulnerability and exploitation of foreign domestic workers.

[For another take on this book, see Lisa’s review]

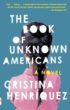

~ Now You See Us, by Balli Kaur Jaswal ~ William Morrow, 2023

Are you recommending “Now You See us”?

Ahaha, my response was the same as Susan S’, did you enjoy the read, do you recommend the book? Singapore’s proportion of foreign workers is more than one third of its population, just under 40%, and this fact is causing a lot of tensions, for all kinds of reasons of course. A most interesting dynamic, at once necessary and exploitative.

Ah, I and my review were ambivalent about the book. I liked the choice of topic, and most of the social commentary was interesting. But it’s not great literature: the murder mystery was unconvincing, and some of the characters were flat. So I’d say read it, because it’s a quick read, but don’t expect too much.