The Silent Patient screams ‘unreliable narrator’ from just about the first chapter.

Alicia Berensen, a beautiful and talented artist, was found one night with a dead husband, a gun with her fingerprints, and slashed wrists. She survived, but has not spoken since. Since this book is set in England, there is no death penalty, and Alicia is now in a mental institution for the criminally insane. Years have passed, and Alicia has not said a word.

Theo Faber, the narrator of this novel, has been fixated with Alicia from the beginning of the trial. He is convinced he can find the key to make her talk and somehow improve her mental health. He goes to the extent of changing jobs so he can work at The Grove, where Alicia is sequestered.

Plot-wise, there is little about this novel that holds together. Despite Theo’s obsessive interest in Alicia, which should have set off red flags in any reasonable doctor, and despite the fact that she has attacked others in the institution, he is allowed to treat her one-on-one. Shortly thereafter she attacks him, but he is still allowed to continue her therapy. Some of the doctors are opposed to reducing Alicia’s medication and the therapy, but they are oddly overruled by the head nurse and one psychiatrist. Theo travels around visiting all her past colleagues and neighbours, all of whom claim to have been ‘very close to her’. Each of them is either in love with her or hates her, and has a reason to frame her for the killing. Each of them is obviously hiding something, but they are all only too willing to talk to Theo.

In case the reader doesn’t pick up the warning signs, Theo’s narrative is full of heavy-handed sentences like:

I resolved to stop at nothing until Alicia became my patient.

I was perfectly able to remain objective about her, stay vigilant, tread carefully, and keep firm boundaries. […] I was wrong. It was already too late, though I wouldn’t admit this, even to myself.

Since Alicia does not speak, there is no easy way for the author to provide her point of view. So after the initial exposition of events (flat, bland), chapters start appearing as outtakes from Alicia’s diary. These are so ludicrous as to be chortle-inducing. They are incredibly detailed and contain long scenes of dialogue, such as:

“How much do you need?”

“Twenty grand.”

I couldn’t believe my ears. “You lost twenty grand?”

“Not all at once. And I borrowed from some people — and now they want it back.”

“What people?”

“If I don’t pay them back, I’m going to be in trouble.”

This is a diary? Alicia, despite her long history of mental problems and delusions, apparently has perfect recall of lengthy conversations. And what’s more, despite her own overriding urge to paint, she takes the time and trouble to write down every spoken word. Needless to say, the police investigators have never seen her diary, but she has somehow kept it with her for years in prison and mental institutions, and helpfully provides it to Theo for the sake of moving the plot forward.

Theo, of course, has his own internal demons: PTSD from a violent unpredictable father, and a wife who appears to be having an affair. This allows him to become equally paranoid and start following his wife around.

The author is a scriptwriter, and it shows. This is a distinctly Gothic novel, peopled by characters who are either stunningly beautiful or creepy, and very much from a male perspective. Scenes are laid out one by one, each person has a secret and smiles cryptically or pauses meaningfully before answering a question.

The writing is pretty pedestrian too. Every voice sounds the same and talks the same way. The ‘psychological insights’ are clumsy, to say the least, and exactly parallel the plot of a Greek tragedy. (In case you miss that, the tragedy, Alcestis by Euripides, is named, described, painted by Alicia, and named on the painting)

Imagine hearing your father, the very person you depend on for your survival, wishing you death. How your sense of self-worth would implode, and the pain would be too great […] so you’d swallow it, repress it, bury it. Over time you would lose contact with the origins of your trauma, dissociate the roots of its cause, and forget. But one day, all the hurt and anger would burst forth, like fire from a dragon’s belly.

Skip this book. It has been optioned for a movie, but I wouldn’t expect much from that either.

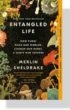

The Silent Patient

Alex Michaelidis

Celadon, 2019.

Well, the novel is definitely plot driven, no two ways about that! You may well be right too about the flat writing that sounds all the same, whichever character! Oh dear oh dear. And yet, I confess, I didn’t not enjoy the read! I probably followed Theo’s obsession with being Alicia’s doctor with perhaps just too much credulity, and not enough critical query. I would agree this is a Gothic style whodunnit. Psychologically gothic, anyway.