~ The Unlikely Adventures of the Shergill Sisters, by Balli Kaur Jaswal ~

Can a pilgrimage to honour their mother’s dying wishes bring three bickering sisters together? And can they also examine the ghosts of their past and face the tumult of their present, while deciding which parts of their identity and cultural baggage to retain and which to drop?

Rajni, Jezmeen and Shirina are three Sikh sisters who grew up in London, and for most of their lives had a widowed mother who struggled to make ends meet after their father died. The girls’ mother, Sita, is in an impossible position. Working two jobs with three children, you can see why she is permanently exhausted and relies on Rajni, the oldest, to supervise the others. At the same time, Sita is thoroughly invested in every traditional custom herself, no matter how patriarchal or narrow-minded, thus effectively diminishing the reader’s sympathy. Her conversation runs along the lines of:

“What kind of daughter-in-law will you make, not even knowing how to cook proper rotis?”

“At least you don’t have to worry like I did, with three daughters.”

When the novel opens, Sita is on the point of death, and has summoned her three daughters for the grand finale. In continuous pain, she still manages to write a long letter, loaded with lashings of guilt, specifying exactly what the girls should do with her ashes, and what’s more, laying out a detailed itinerary for a week-long trip to India.

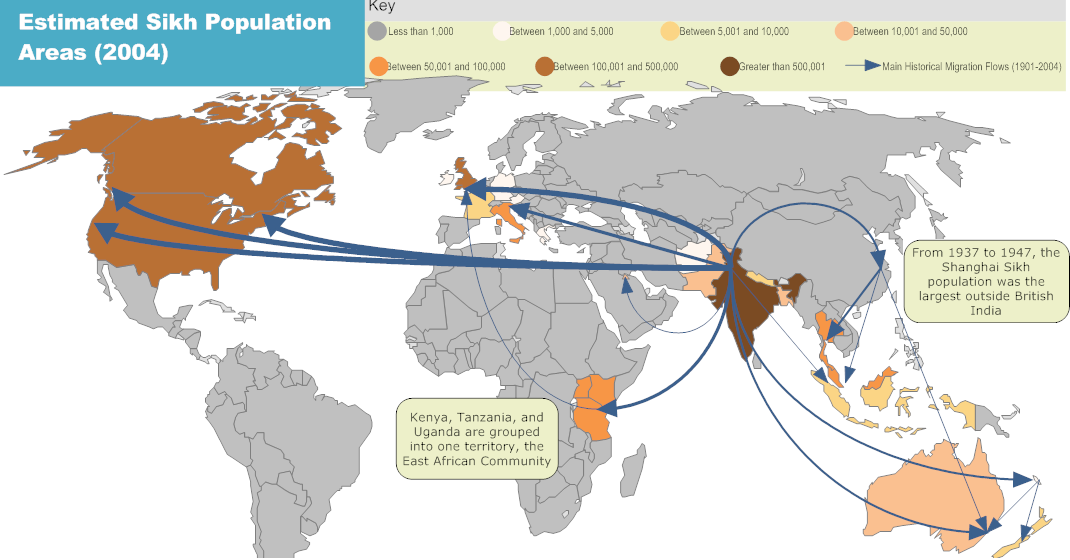

Rajni is married with an 18-year-old son who has just sprung a surprise upon the family. Jezmeen is struggling to find jobs as an actor. Shirina chose an arranged marriage into a wealthy family to escape the bitterness and bickering in her own, but turns out it’s not all roses living with a controlling mother-in-law — from the frying pan into the fire indeed. All three women have secrets in the past and present. Childhood resentments abound. Yet all three head off on the pilgrimage, from England/Australia to Delhi to Amritsar, and back.

The three women are quite distinct characters: Rajni has inherited all her mother’s community-pleasing instincts, Jezmeen is the rebel, and Shirina is so tired from conflict that she has lost her own sense of self in being the peacemaker. Balli Kaur Jaswal does a nice job of writing their conversation in largely recognizable, separate voices.

The author is quite critical of the Sikh community, both in England and India. The Indian Sikhs sneer at the hard working English immigrants (“our people came all the way here to clean toilets?”), they are solidly old-fashioned, and they make fun of the visiting relatives from England (“she talks Punjabi like a gori“). The English Sikh community is not particularly supportive either: Rajni is constantly worrying what “everyone will think”. There is, in general, more kindness to be found from strangers than one’s own relatives.

The men are wimps, never standing up for their daughters or wives. Or, when they have the power, they are oppressive. Shirina’s husband Sehaj:

staying at the office late to avoid hearing about Shirina’s and Mother’s latest conflict, staring at his phone at the dinner table when Mother was giving Shirina a hard time about the quality of her cooking.

(The small accommodations lead to larger: Shirina has to give up her job to look after Mother, and then, just before the trip to India comes a demand that exemplifies the worse of the patriarchy.)

Likewise, the women’s father conveniently avoids conflict. When his brother Thaya-ji criticizes the way Sita and the women behave in England:

“It’s just that you have daughters. You don’t want them learning to talk in such a familiar way to strange men, do you?”

Although Dad looked a bit embarrassed, he shifted in his seat and said nothing.

The older immigrants here are mostly controlling, narrow-minded, traditional parents, who never ever support their children in the face of suffocating community disapproval. Will the next generation be different?

This is an outsider’s gaze at India: although the three women are Sikh, and of Indian origin, their reactions to India, and Indian reactions to them, make it clear that they are visitors. The author writes observantly of the situation for women in Delhi and Punjab: their limited participation in public spaces due to physical danger, the fear of police, who are not necessarily helpful, and may be as dangerous as other men; the well-publicized hideous rape cases of the past decade, the women protesting the lack of safety. The novel also takes on traditional, hard-to-eradicate practices within the Sikh community: female foeticide and male child preference. Indian women in India are peripheral characters here; the focus is on the Sikh-expat sisters and their community.

Balli Kaur Jaswal’s last novel, Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows, was original and often funny, but cluttered and a little uneven. In this, her fourth, her writing has matured and tightened. Perhaps the mysteries are dragged out a little too much for my taste — by the nth foreboding mention of Rajni’s distressing teenage trip to India or Shirina’s anxiety about her mysterious appointment, I was getting as irritable as any of the bickering sisters — and the author’s desire to tie everything up neatly by the end of the novel makes the ending a little predictable, but this is still an entertaining novel with some strong cultural statements to make.

We’ve read this story before — immigrant communities stuck in the past, pushing oppressive customs, conflicts between traditional parents and their second-generation immigrant children — but Balli Kaur Jaswal puts a mostly fresh spin on it.

The Unlikely Adventures of the Shergill Sisters, by Balli Kaur Jaswal. William Morrow, 2019

Loved the review. Been curious about the book and this author, so glad to have your take on it!