~ Unthinkable: An Extraordinary Journey through the World’s Strangest Brains. By Helen Thomson ~

In 1985, neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote a marvellous book: The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. He describes some of the more unusual cases he had seen: a patient with visual agnosia (inability to identify objects, hence the title of the book), people who cannot make new memories, people who do not believe their limbs belong to them, and autistic savants, among others.

Helen Thomson has an updated version in Unthinkable. A neurologist inspired by Sacks but writing 30+ years later, she now has access to much more data from brain scans, neurological studies and genetic discoveries. Sacks described what he saw in clinical settings, but Thomson travels to the patients’ homes, thus aiming to add an additional layer of atmosphere to her stories.

The ten unusual neurological syndromes in her book are undoubtedly fascinating. Among them are:

- People with extraordinary memories, who never forget a day of their lives. If you ask them what happened on the 18th of August in 2005, they can reliably tell you in detail not just the major events that happened around them, but also what they did, felt and saw.

- People with no sense of direction, who can get lost going to the bathroom in a building where they have worked for years.

- People who have startling personality changes after a traumatic brain injury, sometimes becoming more violent, sometimes kinder and calmer, and sometimes wildly creative.

- People with synesthesia — the mixing of senses — who see auras around other people, or associate words or numbers with colours.

- People who have an astounding ability to feel other people’s body movements, twitches, facial changes, and therefore their emotions.

A particularly fascinating chapter is devoted to missing senses and their corollary, overactive senses. Sylvia, who was losing her hearing, constantly hears musical notes. Older people who are losing their sense of smell feel that they are often followed by very strong odours. Normally, the brain spends most of its time filtering out stimuli, because we are exposed to an enormous amount of constant and changing stimuli which would be overwhelming. But when there is an absence of stimuli (for example, when you have a medical problem that causes lack of a particular stimulus), then the brain fills in the space. Most people in a sensory-deprivation chamber start seeing hallucinations within 20 mins. “The brain doesn’t tolerate inactivity “, said Oliver Sacks in 2014.

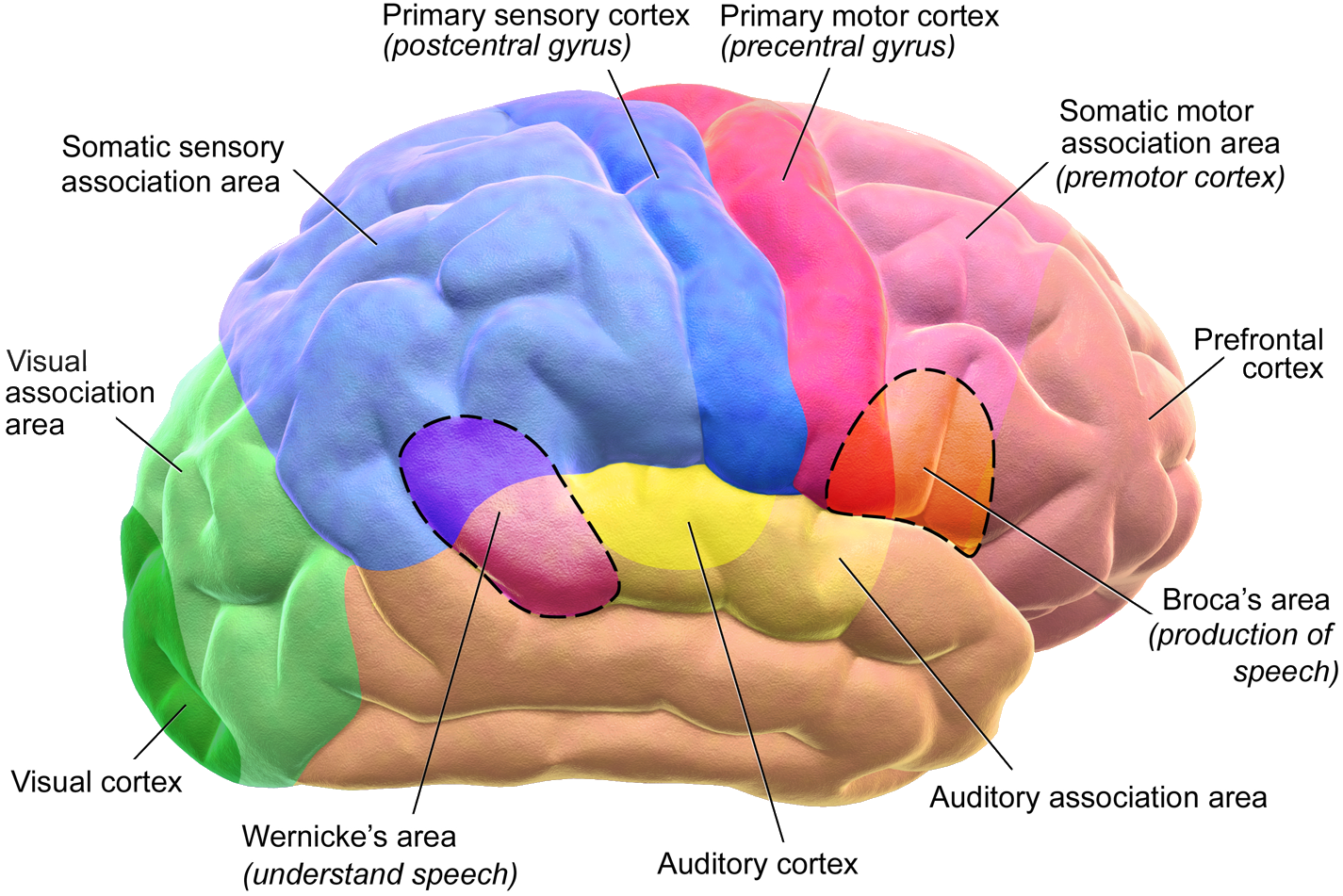

Thomson does a nice job of comparing the truly extraordinary with the somewhat unusual, constantly reminding us that mental abilities are all on a continuum. For example, to contrast the people with no sense of direction, she writes about the London cabbies who have a astonishing mental map of the city. It turns out that these cabbies have a more developed hippocampus, and that this region of the brain is our GPS, with cells that fire when we pass familiar spots.

There are times when one wishes Thomson had probed a little more. The chapter about mirror-touch synesthesia describes people who can feel others’ pain and emotions as if it were their own. Joel, the doctor who has this ability, says his brain mirrors what the people around him feel because of their body motions and twitches. Of course, Thomson, like most people, wants to know how he sees her, and his description sounds awfully like a horoscope — politely positive. But is it accurate? Has Joel been tested in a clinical setting? Thomson spends more time on how he feels about the synesthesia, and on how he sees her, than on the syndrome itself.

One chapter focuses on lycanthropy: people who think they are turning into beasts. Stories of werewolves and their equivalent exist in most cultures, and have been explored by many novelists. In fact, lycanthropy is very rare, and is often associated with schizophrenia.

Thomson writes clearly, and does not talk down to non-scientists. Parts of the brain are described and explained, but then the terms are used throughout the book. Personally, I thought she did better with scientific and clinical description than with ‘atmosphere’. “The streets of Abu Dhabi were hot in the morning sun…. the Rocky Mountains loomed to the north…The rain is lashing down in the seaside town of Brighton” didn’t contribute much in the way of insights or background. Thomson does tend to jump around within each chapter, and inserts herself into the interviews more than I cared for, but that said, most of the people and syndromes she describes are very interesting.

Many readers will want to know if the patients were ‘cured’. Some of them would not want to be treated, and in fact find their unusual brains enhance their lives: Joel, the doctor with synesthesia, says that his ability to empathize with his patients makes him a better doctor even if he has to work hard to not be overwhelmed by the emotions of the sick or dying patients. Some people have learned workarounds to keep the more unusual symptoms under control. And some, sadly, have not done well: the patient who thought he was turning into a tiger seemed to become more schizophrenic, and the man who thought he was dead still seemed intensely depressed at the end of the chapter.

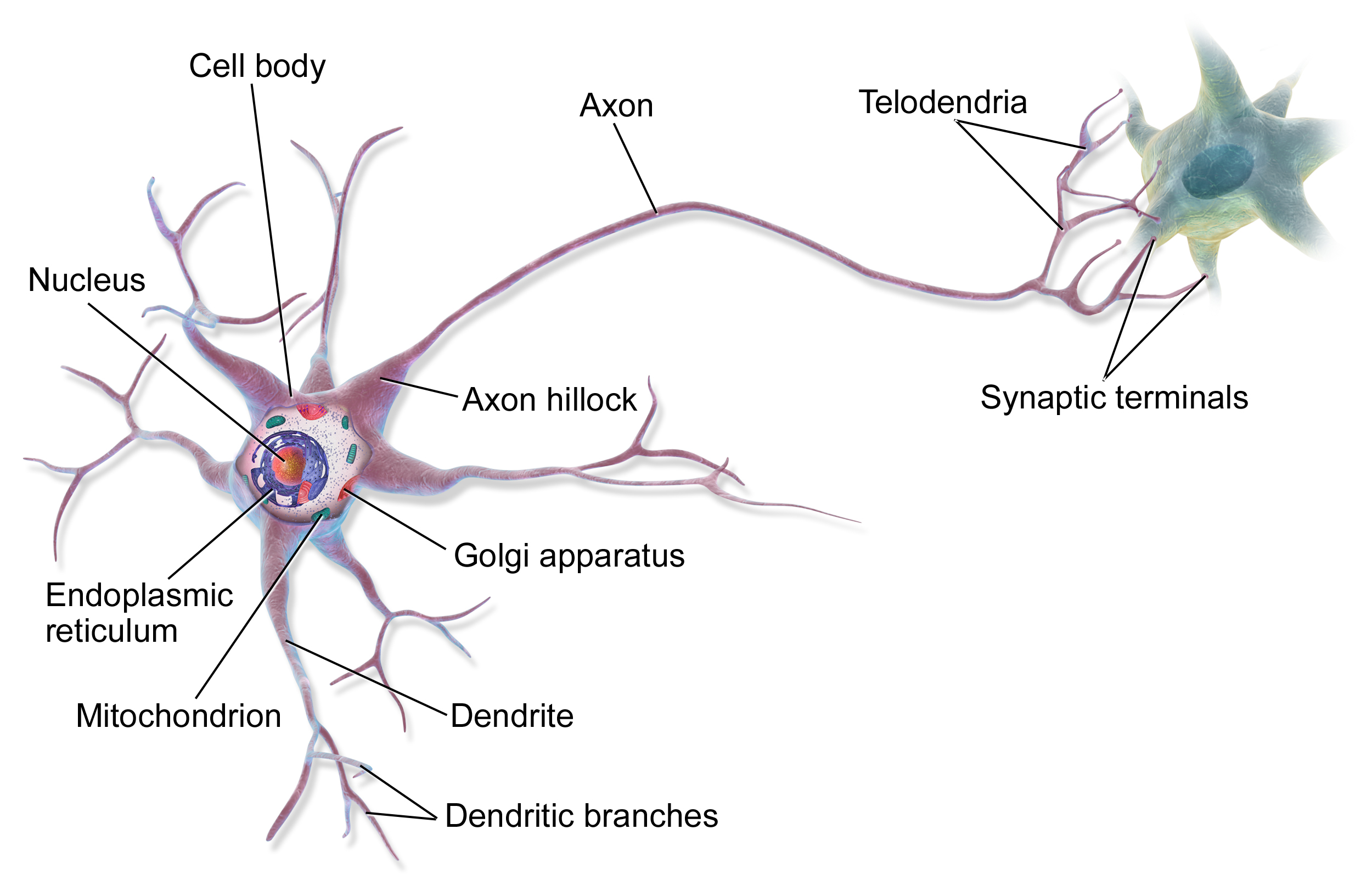

For those of us with boringly standard brains, Thomson provides some clues about what we can change. There are mental tricks to vastly improve your memory, even if we cannot all become Memory Champions. There are hints for those with poor navigational skills. It seems that we can become more empathetic simply by practicing. But what is most striking is how little we still know about the hundred billion neurons we each possess.

Unthinkable: An extraordinary journey through the world’s strangest brains. By Helen Thomson. Harper Collins, 2018

Recent Comments